U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry huddles with his team in Lausanne, Switzerland, April 2015. (Photo: Reuters) |

As soon as Framework Iran was announced, key differences emerged in the interpretation of the original story. The release in Tehran didn't match the screenplays in Washington and Paris, and those versions were incongruent with that seen in Lausanne. At the same time, portions of the framework were hauntingly familiar, leaving audiences and critics with a case of déjà vu. Its uninspired 2015 working title, "Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action" (JCPOA), appeared to be a cheap reprise of the previous release in "The Iran Talks" series, the 2013 "Joint Plan of Action" (JPOA)--as if returning to the same dry well of creativity that produced titles for the "Die Hard" series.

The problem, however, is more than just the name. At its heart, the battle is over which version is authentic. It turns out that Iran's track record of creating a more accurate screenplay that reflects the original story, is far better than the United States. The evidence lies in the previous rollout and ensuing marketing disasters. In fact, it is instructive to review the 2013 JPOA and measure the Obama administration's words against Iranian deeds. In that case, it turned out that Iran's reading was correct and the U.S. was wrong--at least according to the agreement as signed, not as spun.

The announcement of the JPOA was accompanied by the White House public relations rollout, including their fact sheet and talking points. The agreement called for a six-month extension of the nuclear talks with the Obama administration lifting the very sanctions that brought Iran to the table. Surrendering that leverage was a reward for Iran's agreement to continue talking while offering some reversible concessions on its nuclear program.

At its most basic level, the White House claimed their initial understanding "halts the progress of Iran's nuclear program and rolls it back in key respects." Senior administration officials held a background briefing and told reporters that the sum of Iranian concessions added up to "a halt of activities across the Iranian program." This oft-repeated mantra was employed again in President Obama's 2015 State of the Union address: "[F]or the first time in a decade, we've halted the progress of its nuclear program and reduced its stockpile of nuclear material," he declared.

The agreement did no such thing. The Iranians have advanced on each core area of their overall program, namely, their uranium and plutonium paths to a nuclear weapon, and their ballistic missile program. During the interim agreement, Iran continued to enrich uranium up to 3.5 percent--which represents 60 percent of the effort required to produce weapons-grade uranium.

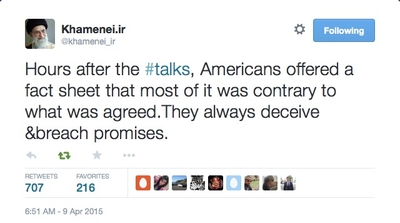

In 2013, the president promised, "If Iran does not fully meet its commitments during this six-month phase, we will turn off the [sanctions] relief and ratchet up the pressure." However, the talks were extended in July 2014 for four months, followed by a seven-month extension in November 2014. There was no corresponding economic pressure leveled by the White House. On the contrary, economic pressure is set to evaporate. The EU and Iran joint statement regarding the new 2015 framework says that in a final deal, nuclear-related sanctions will be terminated "simultaneously" with Iran implementing its obligations; the White House fact sheet says those sanctions will be suspended "after" Iran has taken "all" of its nuclear-related steps. Ayatollah Khamenei's recent speech and tweets only further serve to highlight the diametrically opposed narratives the sides have on this issue.

The White House claimed their understanding with Iran would lead to "increased transparency and intrusive monitoring of its nuclear program" during the interim agreement. But that didn't happen. Last month, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) again declared that Iran was dragging its feet in terms of cooperation. Then came the Wall Street Journal revelation a week before the March 31 deadline that Iran continues to stonewall the IAEA on 11 of 12 issues related to their military's nuclear-related work--uranium mining, enrichment, weaponization, and more. The Journal reported, "in response... the U.S. and its diplomatic partners are revising their demands on Iran."

The White House also declared, "Iran has committed to no further advances of its activities at Arak and to halt progress on its plutonium track." However, a few days later, Foreign Minister Javad Zarif announced, "Iran will press on with construction at a nuclear reactor site at Arak" with Reuters reporting that the move came "despite an agreement with Western powers to halt activity."

Once again, Iran's understanding of the JPOA was correct and the Obama administration was not. State Department spokeswoman, Jen Psaki, admitted that Iran was right about the rather sizable loophole. Nevertheless, she was unconcerned with Zarif's announcement, "whether he meant a road here or an out-building there" because they were not working on the site itself. So while not allowed to bolster the physical reactors themselves, Iran persisted with the construction of parts offsite in preparation for installation.

A National Security Council official told PolitiFact in December 2013 that an Iranian ballistic missile test would "be in violation of the agreement" and cause the deal to "cease to exist." Days later, Iran announced that it would launch yet another ballistic missile some 75 miles into the earth's atmosphere. Shortly thereafter, the White House did an about face and "confirmed that a ballistic missile test would not invalidate the deal" as reported by Adam Kredo, who broke the news in the Washington Free Beacon. Iranian progress on their ballistic missiles has continued unabated with recent assessments putting them on track for significant technological advancements by the end of 2015. They are no longer even a subject in the negotiations.

As for Iran's ability to walk away from negotiations or a deal and breakout towards building a nuclear weapon, the Obama administration's argument--and key metric for measuring success--is that any deal it reaches will keep Iran one year away from obtaining a nuclear weapon. However, just before the JPOA was announced on November 23, 2013, Obama said Iran was a year or more away from having sufficient enriched uranium to produce a nuclear weapon. During President Obama's White House Rose Garden speech hailing the new JCPOA, he said that Iran is "only two or three months away" from having the materials for a nuclear weapon. Contrary to the exaggerated claims, Iran's breakout period has shrunk significantly during the term of the twice-extended JPOA. Read another way, it means that the negotiation process itself is a failure.

Shockingly, in trying to paper over any differences between the sides' view of the JCPOA, an Obama administration official dropped this proverbial bombshell on the New York Times:

American officials acknowledge that they did not inform the Iranians in advance of all the "parameters" the United States would make public in an effort to lock in progress made so far, as well as to strengthen the White House's case against any move by members of Congress to impose more sanctions against Iran.

"We talked to them and told them that we would have to say some things," said a senior administration official who could not be identified under the protocol for briefing reporters. "We didn't show them the paper. We didn't show them the whole list."

That is quite a startling admission. It appears the White House not only knows that Iran's version is more authentic than theirs, but that the administration's exaggerations were concocted with an eye towards pulling the wool over the eyes of the U.S. Congress and the American people.

On the flipside, if Iran's version of what was discussed in Lausanne is incorrect, then it is setting up the coming negotiations for an epic failure by staking out unreasonable positions that will prove impossible to compromise on and subsequently sell to the Iranian people. Either scenario does not bode well for securing a final nuclear agreement by June 30 and maintaining it thereafter.

It remains to note that a year before the 2013 JPOA agreement, President Obama declared that the only deal he would accept is one where "they end their nuclear program. It's very straightforward." Given the president's initially stated stance and where negotiations stand today, it is hard to conclude that the U.S. position hasn't collapsed entirely. Even in the best case interpretation of the newly disagreed JCPOA, it is very likely that the deal will not meet the objective of preventing Iran from gaining a nuclear weapon--and that's without picking apart all of the technical details of the parameters contained in the recent, questionable framework. That essentially means that the battle over which version of the Framework Iran screenplay is more authentic hardly matters since the book itself is so bad.